I was 24 when I first returned to my birth country. Stepping onto the plane that would carry me back to a country I had left 21 years before, I felt dizzy at the convergence of my past and present. Once again I was the 3-year-old girl, traveling halfway around the world to an unknown future in a foreign land — now a woman returning, a foreigner again.

내가 처음 조국의 품에 안긴 것은 24살이었다. 21년 전에 떠났던 나라로 돌아가는 비행기를 밟는 순간 나는 과거와 현재의 한 교차점에서 현기증을 느꼈다. 다시 말하건대 당시 나는 3살이었고, 미래가 확실치도 않은 생판 모르는 나라에 하루의 반나절이나 걸려서 여행을 하였고, 나는 이제 한 여인이면서 한 외국인이 되어서 다시 내가 왔던 그 나라로 여행을 가고 있는 것이었다.

The Land of My Birth was a noisy, clamoring jumble of hip-hop music,televisions, CDs, movies, and billboards tumbling from the streets of Seoul. The South Korea I encountered was a fast-paced, modern, thriving nation choked with smog, street signs, cars and high-rise buildings.Where was the poverty? Where were all the abandoned children? This was not the third world country I had imagined — but it was not the Korea into which I’d been born.

Four years later, in 2000, I had the opportunity to travel with a group of adopted adults back to South Korea on a motherland visit. As part of the tour we visited a baby home in the southern city of Cheonju. All the children were under the age of 4 and, for various reasons, none were available for international adoption. It was then I began to truly understand my humble beginnings and the complexities of adoption as an intervention for children who have lost their primary caregivers.

4년 뒤인 2000년에 성인 입양 그룹과 함께 한국으로 여행을 갈 기회가 있었다. 여행 코스로 우리는 청주에 있는 어린이 집을 방문했다. 아이들은 다 4살 이하의 아이들이었고 다 사연이 있는 그럼에도 해외 입양은 가능하지 않은 상태였다. 그 때 나는 보호를 잃은 아이들을 위해 중재하는 입양의 복잡성에 대해 알기 시작했다.

As our bus pulled up to the orphanage and we stepped onto the paved playground, a row of little faces peered up through the doors, palms pressed against the glass in anticipation of our visit. Tears began to fall immediately as the adopted adults looked for and saw our own reflections in their tiny faces.

우리가 탄 버스가 고아원에 서자 포장된 놀이터로 들어 갔고 작은 아이들의 행렬이 문에 보이기 시작했다. 아이들은 우리의 방문을 기대했는지 손바닥을 유리창에 대고 서 있었다. 갑자기 눈물이 콱 쏟아졌다. 입양 되어 성인이 되어 여기 서 있는 우리들은 자신들이 이 작은 아이들의 얼굴에서 반사 되어 보이는 것을 보았다.

At that time I had no training in child development or social work but I noted their behavior. I was struck by how little the children produced words. There was an eerie absence of kids’ voices in the playroom, filled instead by the chirping television. Some of the children recoiled from hugs. Others seemed to cling to my body, sucking the warmth and reassurance of human contact, if only for a few hours. A few would pierce me with their eyes and ignore me, seeming to know I would leave them like others had before.

그 당시 나는 아동 발달과 사회사업에 대한 지식이 없었으나 아동들의 행동들을 기록했다. 나는 그 아이들이 단어를 만들어 내지 못한다는 사실을깨달았다. 시끄러운 텔레비전 소리로 가득한 놀이방에서는 유아들의 목소리가 섬뜩할 정도로 없었다. 몇몇 아이들은 포옹에 움찔했다.다른 몇 몇 아이들은 온기를 빨아들이는 듯이, 인간 접촉으로 안심하려는 듯이 내 몸에 매달렸다, 단지 몇 시간 동안이었지만.소수의 아이는 눈으로 나를 뚫어지게 쳐다 보았고 나중에는 나를 무시했다. 내가 과거의 다른 사람들처럼 자신들을 떠날 것이라는 사실을 아는 것처럼.

It was clear that the caregivers at the orphanage cared for the children, but there were simply not enough of them to provide the individual attention each child needed. Looking at those children I could not help but think: I got out.

보육원의 보육자들이 아이들을 돌본 것은 확실하지만, 아이들에게 개인적인 관심을 두기는 각기 개인이 필요한 개인적인 관심사를 다 제공하기에는 충분치가 않는 그런 것이 있었다. 내가 그 아이들을 바라 보면서 내가 도움을 줄 수는 없는 그러나 생각은 할 수 있었다.: 나는 밖으로 나갔다.

And it made me wonder: Why with all the wealth in Korea were these children here? What were their prospects growing up as orphans? And who were their advocates? Who could speak for their needs and best interests? Who would ensure that they would get to live to their full potentials — and not simply survive? I decided that I would.

그리고 나서 그런 것들은 나에게 궁금증이 생기게 했다. : 왜 한국의 잘 사는 사람들은 아이들을 여기에 있게 할까? 고아로 성장함으로써 무슨 전망이있을까? 그리고 누가 그들의 지지자가 되어줄까? 누가 그들이 필요한 것들과 최고의 관심사들을 말할 수 있을까? 그들이 가진 충분한 잠재력을 발휘하면서 살도록 누가 책임을 지고 있는가? - 이것은 단순한 생존만이 문제가 아니다. 나는 내가 그렇게 하겠다고 결심했다.

By the time I completed my masters of science at Columbia University School of Social Work in 2003, I had learned why the children I had seen in the orphanage behaved the way they did. Current research on children in Romanian orphanages has provided unequivocal evidence of the detrimental effects of institutional care on a child’s development.

2003년 나는 콜롬비아 대학에서 사회사업 석사 학위를 마칠 때까지 보육원에서 보았던 아이들이 그런 식으로 행동하는지에 대해 배웠다. 루마니아 보육원에서 아동에 대한 현재의 연구는 제도적인 보호가 아동 발달에 해로운 영향을 미친다는 명백한증거를 제공하고 있다.

The fact is the quality of caregiver-infant relationships in the first years of life may be more important than the quantity of nourishment in facilitating healthy human development. In other words,children who experience the deprivation of a primary caregiver are at a greater risk for suffering from emotional, behavioral and cognitive problems that may impair their long-term ability to form healthy relationships, learn, or work in meaningful ways — a condition that can be remedied by the permanency of adoption.

사실, 처음 일 년간 보육자의 질과 유아 간의 관계는 건강한 인간 발달을 쉽게 하는 영양보다 더 중요하게 보인다. 다시 말해, 처음의 보육자를 박탈당한 경험을 한 아이는 감정, 행동 그리고 인지력에 커다란 손실을 겪게 된다. 그 손실은 입양된 존재로서 치료를 받을 수 있는 상태로서 삶의 중요 방식인 건강한 관계, 학습, 또한 직업을 형성하는 오랫동안의 능력을 해치는 것이다.

Historically, inter country adoption began as a humanitarian response to the immediate plight of children in the aftermath of armed conflicts, political and economic crises, and social upheavals.Although the first international adoptions occurred after the Second World War, it was the adoption of children — many born to Asian mothers and U.S. soldiers — at the end of the Korean War (1950-53) that initiated the widespread practice of international adoption known today.

한국은 가장 오랫동안 국외입양 프로그램을 운영하고 있고 다른 어떤 나라보다도 가장 많은 아동을 입양을 위해 국외로 보내왔다.한국 보건복지부의 공식적인 통계에 따르면, 1953~2006년 사이 15만 944명의 아동이 국외로 입양되었다. 그 중 10만4천319명의 아동은 미국 시민으로 입양되었다. 대략 한국계 미국인의 10명 가운데 1명 정도이다.

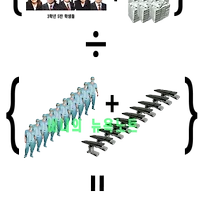

Today, it is being argued that South Korea has the economic wealth to take care of her own children and should abolish the practice of inter country adoption. It has been trying. In 1996 the South Korean government revised its adoption law stipulating an annual decrease of international adoptions by 3 to 5 percent, with an eventual phasing out by 2015. Since then the number of Korean children sent overseas for adoption has hovered around 2,000 children annually.

오늘날, 한국은 경제적 성장을 하게 되어 자기 나라의 아이들을 스스로 돌보고 국가 간 입양제도의 실천을 폐지해야 한다고 주장하고있다. 1996년 한국 정부는 2015년까지 매년 3~5%씩 국외 입양을 감소하는 입양법을 수정했다. 1996년 이후 한국아동이 국외로 보내진 숫자는 매년 2천 명 정도에서 맴돌고 있다.

As in the past, these changes reflect broader social and political realities. South Korea’s inter country adoption program has historically been tied to its population problems. Unlike the past, Korea now faces low population growth at the same time it is encouraging domestic adoptions. In 2006 the government rolled out a five-year welfare strategy to tackle the country’s low birth rates. It includes financial incentives to adults who choose to adopt and give birth. And as of January 2007, children available for adoption must wait at least five months for a possible domestic placement before being considered for inter country adoption.

과거처럼, 이러한 변화는 폭넓은 사회적, 정치적 현실을 반영하고 있다. 한국의 국외 입양 제도는 역사적으로 인구문제와 깊은관련을 맺어 왔다. 과거와 다르게, 한국은 지금 국내 입양을 장려하고 있는 동시에 낮은 인구 증가에 직면하고 있다. 2006년에한국 정부는 국가의 저출산율을 방지하기 위한 5개년 복지 전략을 세웠다. 이 전략에는 입양과 출산을 선택한 성인에게 재정적인 지원을 해주는 것을 포함하고 있다. 2007년 1월 입양되는 아이들은 국외 입양이 되기 전에 가능한 한 국내에서 적어도 5개월을 대기해야 한다.

Despite these efforts, of the 9,420 children available for adoption in 2005, only 1,461 were adopted domestically while 2,101 children were allowed to be adopted overseas. So what happened to the nearly 6,000children who did not get adopted domestically or abroad?

이러한 노력에도 불구하고, 2005년 입양되어야 하는 9천 420명의 아이 가운데 단지 1천 461명 만이 국내 입양이 되었고,2천 101명의 아이는 국외로 입양되었다. 국내나 국외로 입양되지 않은 나머지 6천여 명의 아이에게는 무슨 일이 일어났을까?

According to statistics of the Korean Ministry of Health and Welfare the number of children entering orphanages has risen from 17,675 in2004 to 19,000 in 2007 with about 800 to 900 18-year-olds every year aging out of the system with little housing, educational, or vocational support. As in the U.S. foster care system, these children get tore main in their country of origin but with little opportunity to reach their full potential.

한국 보건복지부의 통계에 따르면, 보육원에 입양된 아동 숫자는 2004년에 1만 7천 675명, 2007년에 1만 9천 명이발생했고, 집, 교육 또는 직업 지원이 거의 없는, 시스템 밖에 있는 18세 청소년이 매년 800명~900명 정도이다. 이 아동들은 자신들의 잠재력을 계발할 기회를 거의 갖지 못한 채 자기 나라에 남아 있다.

Today, birth mothers in Korea do not have a level playing field because the choice for a single, unwed mother to parent simply does not exist — not only because the government provides only nominal financial support to single mothers, but because the entire society rejects them.

오늘날, 한국에서 임신한 엄마는 하나의 활동 분야를 갖지 못한다. 왜냐하면 독신과 미혼모를 위한 선택은 존재하지 않기 때문이다.그뿐 아니라 정부는 모자 가정에 대한 명목상의 재정적인 지원이 거의 없고 전 사회가 그들을 거부하기 때문이다.

Not so long ago in America we treated our single, unwed mothers in quite the same way. It took Americans 20 years and a women’s movement before we transformed old attitudes and beliefs; I would think it will take South Korea at least that much time and they are already making some progress.

미국에서 오래전에 그랬듯이 독신과 미혼모를 같은 방식으로 대우하지 않는다. 미국의 여성 운동은 이런 태도와 관습을 바꾸는 데 20년이 걸렸다. 나는 한국도 더 많은 시간이 걸릴 것이고 이미 약간의 진보를 거둔 것으로 생각한다.

In a nation where one in three South Korean parents are willing to send their children abroad for the sake of a better education, it does not surprise me that inter country adoption has remained entrenched in society. And I hope it will continue.

세 명의 한국 부모 중에서 한 부모는 아이들을 더 나은 교육을 하려고 국외로 기꺼이 보낸다. 국외 입양이 사회에 굳건하게 남아있다는 것은 나에게 놀라운 일이 아니다. 그리고 나는 국외 입양이 계속되기를 희망한다.

South Koreans have often felt shame for its long history of international adoption, but we in the United States also allow some of our children to be adopted overseas, an estimated 500 annually. Mostly these are children voluntarily relinquished by their parents to mostly other Western nations. But Americans also adopt on average in any given year 50,000 children from our domestic foster care system, a far greater number than the current rate of domestic adoption in South Korea.

한국은 때때로 오랜 국외 입양에 대한 수치를 느끼고 있으나, 우리 미국은 국외로 입양되는 아이들을 매년 500명 정도 허용하고 있다. 부모들에 의해 자발적으로 단념된 아이들이고, 대부분 서구 국가들에 입양되고 있다. 그러나 미국인들은 또한 국내 육성 보호시스템에 의해 5만 명 정도의 아이들이 입양되고 있다. 이 숫자는 한국에서 국내 입양되는 현재의 비율보다 더 많다.

Ultimately, the challenge is how to balance the need to respect a child’s right to his or her ethnic identity and cultural background against the known detrimental effects caused by early deprivation of a primary caregiver. Such issues and others were discussed at length at the recent "Adoption Ethics and Accountability: Doing it Right Makes a Lifetime of Difference.", conference held in October and co-sponsored by the Even B. Donaldson Adoption Institute where I work as the policy director.

궁극적으로, 그 도전은 중요한 보육자의 초기 박탈에 의해 일어나는 해로운 영향을 차단하는 민족적 정체성과 문화적 배경에 대한 아이들의 권리를 존중하는 필요성에 균형을 맞추는 일이다. 이런 문제들이 "입양 윤리와 책임: 일생의 차이를 올바르게 만드는일"이란 주제로 지난 10월 개최된 회의에서 충분히 논의되었다. 이 회의는 내가 정책 책임자로 일하는 에반 B. 도날드슨 입양기관에 의해 후원되었다.

Personally, I am not for adoption or against it. I can see its value and also its limitation. What I am for are choices. The argument for me is not whether international adoption should be abolished or promoted,but rather how to maximize options for children so that all can reach their full potential, be it with those who bore them or those willing to adopt them at home or abroad, or for those children who have no option but to grow up in an institution.

개인적으로, 나는 입양에 찬성하거나 반대하지 않는다. 나는 입양의 가치와 그 한계를 볼 수 있다. 내가 찬성하는 것은 선택이다. 나의 관심은 국외 입양이 폐지되거나 증진되어야 한다는 데 있지 않고, 오히려 충분한 잠재력이 계발되는 아이들의 선택권을 최대화하는 데 있다. 또, 아이들을 싫어하는 사람들 또는 국내나 국외에 아이들을 기꺼이 입양하는 사람들 또는 선택권이 없지만 입양 기관에서 성장해야 하는 그런 아이들에게 있다.

참고: http://relativechoices.blogs.nytimes.com/2007/11/27/south-korea-and-its-children/

번역: 파랑새

이렇게 가치있는 글을 쓴 사람에게 전한다. God bless you!

리치 멀린스의 생애와 "Step By Step (Sometimes By Step)"